Posted in Marine industry talk

As the celebrations surrounding IMO’s 70th anniversary fade into memory, it is one of the industry’s worst kept secrets that the UN agency’s Energy Efficiency Design Index requirements have failed to keep pace with improvements in vessel design and operation.

Owners can be swift in adopting efficiency measures when cash is on the line but, for some, environmental regulations prompt only a sigh of resignation that something will need to be done when the rules change. However, when IMO adopted EEDI in 2011 and outlined its scheduled phase-in, the ambition was to set vessels on a course towards improved efficiency that would be of benefit to shipping as a whole.

So far, the results have been underwhelming. Periodic reviews of targets have attracted criticism – and not infrequently ridicule – for setting the bar too low to incentivise vessel owners to explore and implement substantive changes to vessel design.

So what went wrong? Imbued with the spirit of ‘kaizen’, the Japanese management philosophy of ‘continual improvement’, EEDI is fundamentally a ratchet mechanism with successively tougher efficiency targets agreed and phased in over time. These targets must be challenging but, with a nod to the myriad other pressures on ship owners, attainable.

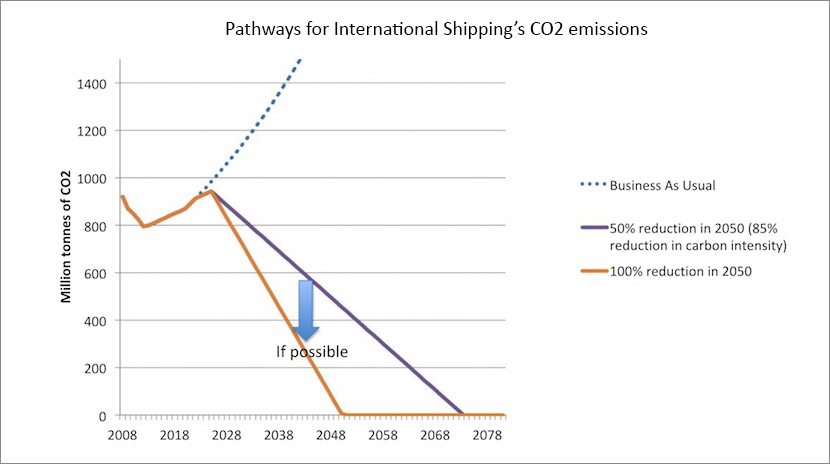

Source: UCL Energy Institute

According to the sponsors of a paper due to be presented for consideration by August’s MEPC, IMO’s twice-yearly gathering on environmental matters, the problem lies with insufficient numbers of owners telling IMO how their ships are performing. The sponsors, a cluster of NGOs, including ICS and BIMCO, and heavyweight Member States Japan and Norway argue that this lack of data reaching the IMO EEDI database is undermining the index.

Verified data on the existing fleet is essential for trend analysis and setting realistic goals for the next round. Without it, either the system grinds to a halt, or as the paper’s sponsors suggest, new targets are determined based on an unrepresentative, and potentially misleading sample, with policymakers forced into making some dangerous assumptions as they attempt to fill the gaps. Which perhaps explains the degree of caution evident in the current targets.

The sponsors corroborate their position by presenting a sector-by-sector comparison of the number of ships entered into the EEDI database against the number of newbuilds registered in commercial databases maintained by reputable market analysts, which indeed reveals some stark anomalies. This forgetfulness to supply details seems especially odd given the vast array of EEDI calculators available on the market. In fact, performing the necessary calculations by hand shouldn’t be beyond the capabilities of a competent naval architect.

The sponsors propose a very straightforward solution: that EEDI should become mandatory. In addition to reporting the index value for each newbuilding, they propose ship owners should briefly list design elements or changes that assisted them reach their attained EEDI, to give policymakers a richer picture of what measures are producing what results.

There is some irony in the fact that a mechanism introduced to improve efficiency is itself operating inefficiently. However, if the lack of data truly is the root cause of its current shortcomings, it may be time to accept that, left to its own devices, shipping will not participate in a way that supports a meaningful EEDI.

In August, it is likely that debate at and around MEPC will veer towards the coming 2020 cap on fuel sulphur content, or IMO’s roadmap for decarbonisation to 2050 and beyond. However critical for shipping, it would be a mistake if the focus on these topics led to the unravelling of EEDI [and its sibling SEEMP for vessels in-service], given the hard yards put into devising a workable scheme in the first place.